Uterine abnormality - problems with the womb

Some women have a womb (uterus) that is different in shape or size from the norm. This is called abnormality of the womb or congenital uterine abnormality. It means that your womb (uterus) formed in an unusual way before you were born.

Many women have a differently shaped womb but are unaware as there often aren’t any symptoms. You may only find out during an ultrasound scan or if you’ve experienced miscarriage, bleeding or difficulties conceiving. Some women have told us that knowing about a womb abnormality has helped them to plan and prepare for pregnancy.

Although these abnormalities are quite common, the effect they have on pregnancy isn’t always clear. Having a womb abnormality won’t always affect your ability to become pregnant, but it may be more difficult for you to carry your baby to full-term. Depending on the shape of the womb, there may be an increased risk of miscarriage or preterm birth (giving birth before 37 weeks). Womb abnormality can also be linked to a weaker cervix (sometimes called cervical incompetence), which can lead to preterm birth. You may need extra monitoring during pregnancy to keep you and your baby safe.

On this page, we explain the different types of womb abnormalities and the effects they may have on pregnancy. Reading about these increased risks may be scary but try to remember that many women do manage to get pregnant and have a healthy baby. Your healthcare team will be able to support you throughout your pregnancy to help reduce any risks.

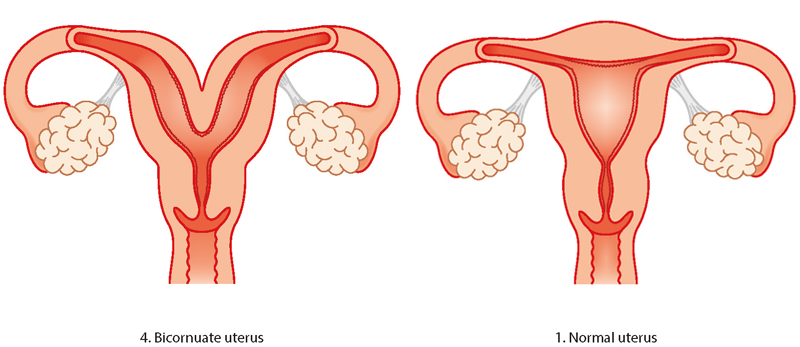

Bicornuate womb

A bicornuate womb has a deep indentation at the top. Women with a bicornuate womb have no extra difficulties with conception or in early pregnancy, but there is a slightly higher risk of miscarriage and preterm birth. It can also affect the baby’s position later in the pregnancy so a c-section (caesarean) might be recommended.

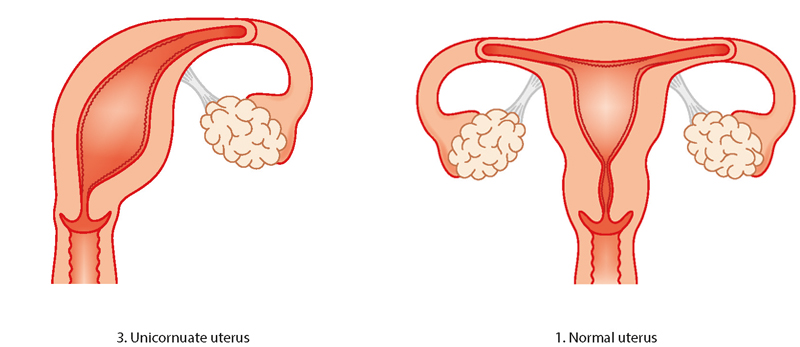

Unicornuate womb

Having a unicornate womb is rare. It means your womb is half the size of a normal womb because one side didn’t develop. There is an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy (an abnormal pregnancy that implants and develops outside the womb), late miscarriage or preterm birth. The baby may lie in an awkward position in later pregnancy so a c-section (caesarean) might be recommended. Women who have unicornate wombs can conceive, although unicornuate wombs are more common in women who are infertile.

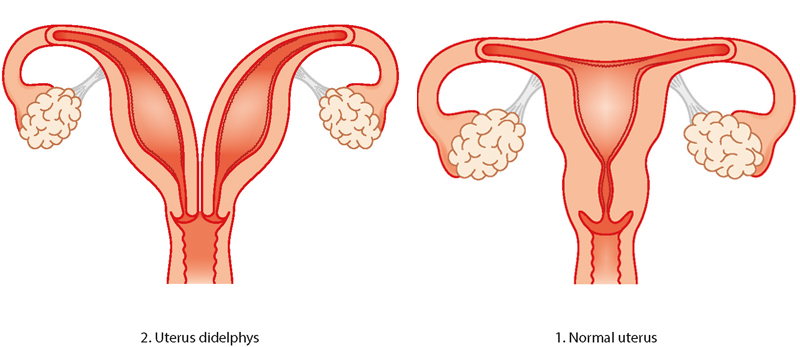

Didelphic (double) womb

The didelphic womb is split in two, with each side having its own cavity. This usually affects the womb and cervix, but it can also affect the vulva, bladder, urethra and vagina. Women with a didelphic womb have no extra difficulties with conception and it is only linked to a small increase in the risk of preterm birth.

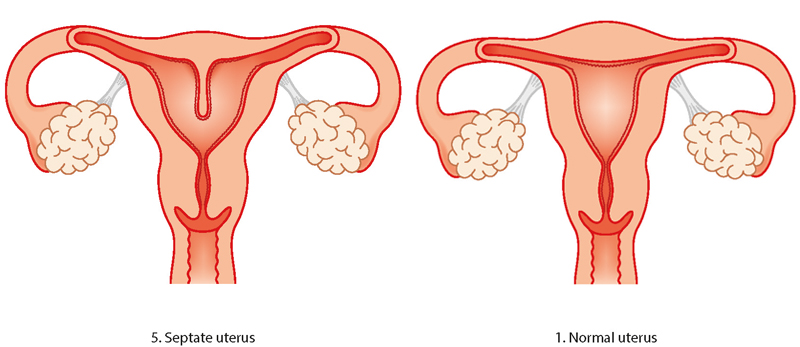

Septate/subseptate womb

A septate womb has a wall of muscle coming down the centre splitting the space in two. Sometimes the wall only comes part-way down the womb (subseptate) and other times it comes the whole way down (septate). Women with subseptate or septate wombs are more likely to have difficulties with conception. There is also an increased risk of early miscarriage and preterm birth. In later pregnancy, the baby may not be lying in a head-down (cephalic) position so you may be advised to have a c-section.

“When I was first diagnosed with a septate uterus, I was petrified. I read a lot of scary information online about the risks associated with a septate uterus. My consultant reassured me that a lot of women have congenital uterine abnormalities and are not aware. I read online that a lot of women with a septate uterus have surgery to resect the septum before pregnancy. My consultant did not recommend this. Despite having a complete septate uterus, I was able to carry my baby to term. He was breech, so I did have an elective c-section. I wish I would have trusted my consultant more and not believed everything I read online.”

Emma

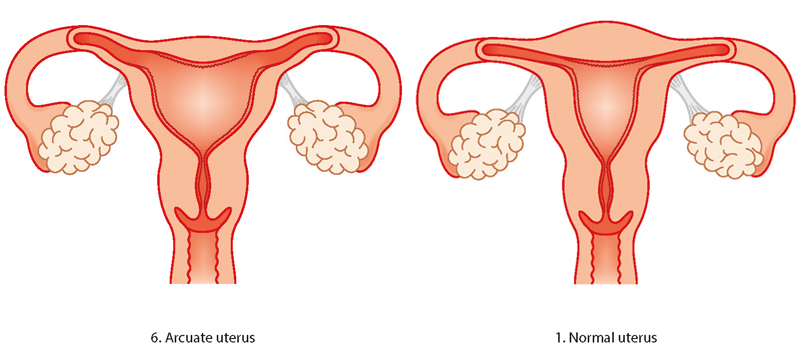

Arcuate womb

The arcuate womb looks very like a normal womb but it has a dip at the top. Having an arcuate womb doesn’t increase your risk of preterm birth or early miscarriage but it may increase your risk of late miscarriage. In later pregnancy, your baby may not be lying head down so you may need to have a c-section.

How will I know if I have an abnormal womb?

Most women don’t know that they may have an abnormally shaped womb when they become pregnant as it’s unlikely that they will have any physical symptoms in early pregnancy. You might only find out when you have difficulty conceiving or when you have an ultrasound scan after experiencing a miscarriage. Some women may find out about their abnormal womb if they’ve previously had investigations after recurrent miscarriage or gynaecological problems such as abnormal bleeding.

If you have a didelphic (double) womb or a unicornuate womb, it may be identified during routine pregnancy scans. However, routine pregnancy scans may not identify milder forms of womb abnormality.

Investigations can include a hysteroscopy, a laparoscopy or a three-dimensional pelvic ultrasound scan.

Hysteroscopy

A hysteroscopy is a procedure to examine the inside of the womb. It involves placing a small camera through the cervix into the womb cavity. Fluid is flushed inside the womb to allow a view of the whole womb cavity. During this procedure, the doctor can look at the shape of the womb as well as any other abnormalities such as fibroids or polyps.

There are some small risks associated with hysteroscopy. These include bleeding, infection, damage to the cervix and perforation of the womb (where a hole is unintentionally made in the wall of the womb). However, these risks are uncommon. Your doctor will talk to you about these risks in detail before the procedure and you will need to give your consent. After the hysteroscopy, it is normal to experience some period-type pains and some light vaginal bleeding for a few days afterwards.

If you have had recurrent early miscarriages (3 or more) or one or more second trimester miscarriage, your healthcare team may suspect that you have an abnormally-shaped womb. They may offer you a pelvic ultrasound, MRI scan or laparoscopy to look at the shape of your womb. Sometimes, a hysterosalpingogram might be offered. This is when an x-ray visible liquid is injected through the cervix and pictures are taken using an x-ray to see the flow of the liquid around the womb and fallopian tubes.

The NHS has lots of information about having a hysteroscopy.

Laparoscopy

A laparoscopy is a surgical procedure that allows a surgeon to access the inside of the tummy cavity. A camera is inserted through the abdominal wall to view the womb, tubes and ovaries.

The NHS has lots of information about having a laparoscopy.

A pelvic ultrasound scan

A pelvic ultrasound uses sound waves to view the womb. A ‘transvaginal’ ultrasound is preferred as the sound waves are closer to the womb and ovaries. This is performed by placing a probe inside the vagina to view the womb and ovaries. This may be uncomfortable but shouldn’t take long.

The NHS has lots of information about having an ultrasound.

What is the treatment for womb abnormalities?

The treatment of womb abnormalities depends on the type of abnormality that you have. Although surgery might sound like a good plan, operations can sometimes lead to later infertility and problems occurring during the pregnancy. A gynaecologist will usually discuss any treatment options with you if a womb abnormality is identified before a pregnancy.

If you are diagnosed with an abnormally shaped womb during pregnancy, you will be put into the care of an obstetric team. You will have extra scans and hospital visits to check up on you and your baby throughout the pregnancy.

If your baby ends up in an awkward position (lying across your womb or bottom first) in later pregnancy, your healthcare team will talk to you about your birth options. They will probably recommend that you have a caesarean section, but it’s your decision.

How can I cope during my pregnancy?

If you know you have an abnormally shaped womb, you may feel anxious during your pregnancy, especially if you’ve previously had a miscarriage or premature baby.

It’s important to go to all your antenatal appointments so you can have all the relevant tests and scans. If you feel that something is wrong, contact your midwife or hospital straight away. Don’t worry about raising a false alarm. Your midwife would rather make sure that you and your baby are safe.

It's also good to know the signs of preterm labour, if you think your baby is coming too soon.

- Caserta, Donatella et al. “Pregnancy in a unicornuate uterus: a case report.” Journal of medical case reports vol. 8 130. 29 Apr. 2014, doi:10.1186/1752-1947-8-130.

- Chan, Y. Y., Jayaprakasan, K., Tan, A., Thornton, J. G., Coomarasamy, A. and Raine-Fenning, N. J. (2011), Reproductive outcomes in women with congenital uterine anomalies: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 38: 371–382. doi: 10.1002/uog.10056.

- Mastrolia SA, Baumfeld Y, Hershkovitz R, Yohay D, Trojano G, Weintraub AY. Independent association between uterine malformations and cervical insufficiency: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018 Apr;297(4):919-926. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4663-2. Epub 2018 Feb 1. PMID: 29392437.

- NHS. Hysteroscopy. Page last reviewed: 05 December 2018, Next review due: 05 December 2021.

- Reichman D, Laufer MR, Robinson BK. Pregnancy outcomes in unicornuate uteri: a review. Fertil Steril. 2009 May;91(5):1886-94. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.163. Epub 2008 Apr 25. Erratum in: Fertil Steril. 2015 Jun;103(6):1615-8. PMID: 18439594. RCOG (2011) Recurrent Miscarriage, Investigation and Treatment of Couples. Green-top Guideline 17. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

- Tulandi T, Al-Fozan HM. 2020. Management of couple with recurrent pregnancy loss. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com