Waters breaking early (PPROM)

This page covers waters breaking early before 37 weeks.

Read more here about what to expect when your waters break after 37 weeks.

What is preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes (PPROM)?

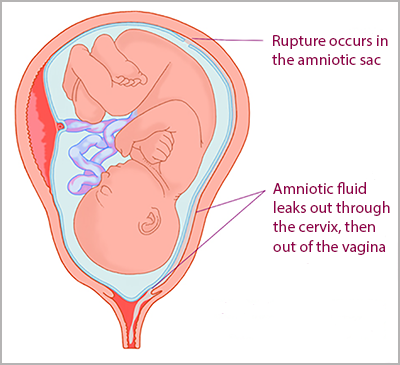

Your baby develops inside a bag of fluid called the amniotic sac. When your baby is ready to be born, the sac breaks and the fluid comes out through your vagina. This is your waters breaking.

It is also known as "rupture of the membranes".

Normally your waters break shortly before or during labour. If your waters break before than 37 weeks of pregnancy, this is known as preterm pre-labour rupture of membranes or PPROM.

If this happens, it can (but does not always) trigger early labour.

Is PPROM common in pregnancy?

PPROM happens in around 3 out of 100 of pregnancies.

PPROM is also linked with 3 to 4 out of every 10 premature births (where the baby is born before 37 weeks)

What causes PPROM?

We don’t always know why PPROM happens.

It may be caused by infection, or by problems with the placenta, such as placental insufficiency (where the placenta does not develop properly) or a blood clot (haematoma) behind the placenta or membranes.

You may also be more at risk of PPROM if you:

- have had a premature birth or PPROM before

- have had any vaginal bleeding in pregnancy

- have had any direct trauma (such as a bump or a blow) to the stomach

- have had cervical surgery or have a short cervix

- aren't getting enough nutrition

- are underweight (have a low body mass index or BMI)

- have experienced placental abruption before

- have extra fluid around the baby in the amniotic sac (polyhydramnios)

- are pregnant with more than 1 baby.

There is also some evidence to suggest that Black and Black Mixed-Heritage pregnant people might be more at risk of PPROM. However, the evidence for this isn’t clear and more research is needed to understand if ethnicity impacts the chance of having PPROM

In most people, the exact cause of PPROM is unknown. It is important to remember that PPROM is not caused by anything you did or didn’t do in pregnancy.

How will I know if my waters have broken?

Your waters breaking may feel like a mild popping sensation, followed by a trickle or gush of fluid that you can’t stop, unlike when you wee.

- The amount of fluid you lose may vary.

- You may not have any sensation of the actual ‘breaking’, and then the only sign that your waters have broken is the trickle of fluid.

- It doesn’t hurt when your waters break.

You can read more about what to expect when your waters break.

What should I do if my waters break early?

If you think your waters may have broken, you should contact the maternity unit or labour ward and go to the hospital for a check-up straight away.

Amniotic fluid is clear and a pale straw colour. It may be a little pinkish if it contains some blood, or it may be clear.

You must tell your healthcare professional if:

- the waters are smelly or coloured

- you are losing blood.

This could mean that you and your baby need urgent attention.

If you think that you are leaking fluid from the vagina, wear a pad not a tampon so your doctor or midwife can check the amount and colour of your waters.

“I had cervical incompetence and PPROM. I was put on hospital bedrest, antibiotics and had regular scans on the remaining water levels. Despite the antibiotics my infection markers were getting worse and I had to be induced at 24 weeks because they didn't think my baby would survive much longer in an infected womb. He survived birth, spent 7 months in hospital and then came home. He's now almost 5 years old and starting school in September.”

Rachel

Checking for PPROM

When you arrive at hospital, your healthcare professional will assess you to see if your waters have broken.

- This will usually involve a vaginal examination and you will be asked details about the fluid loss.

- A doctor or midwife will also check on your general health including your temperature, pulse and blood pressure.

- They will also check your baby’s heartbeat and may do a urine test to check for infection.

- Your healthcare professional will talk to you about what has happened, how you are feeling and your pregnancy history.

How is PPROM diagnosed?

If PPROM is likely your healthcare professional will usually ask to do an internal vaginal examination. They will ask for your permission before doing so.

You may have what’s called a speculum examination. This is when a small instrument covered in gel is inserted into the vagina.

The healthcare professional will then be able to see if there is any fluid pooling in the vagina. They will also take a swab to test for infection and a swab to test for Group B strep (GBS) infection.

This will help confirm if your waters have broken. This test isn’t usually painful but it can sometimes be uncomfortable.

If it isn’t clear from the speculum examination, they may do a swab test of the fluid. They may also do an ultrasound scan to estimate the amount of fluid around your baby.

If your waters are shown not to have broken, you should be able to go home.

If only a very small amount of amniotic fluid is leaking, it is not always possible to see it during an examination and it can be difficult to confirm whether your waters have broken.

If you continue to leak fluid at home, you should return to the hospital for a further check-up.

Treatment of PPROM

If your waters have broken, you will usually be advised to stay in hospital where you and your baby will be closely monitored for signs of infection. This may be for a few days or maybe longer.

You will have your temperature, blood pressure and pulse taken regularly, as well as blood tests to check for infection. Your baby’s heart rate will also be monitored regularly.

Your healthcare professional will discuss with you the possible outcomes for your baby. These will depend on how many weeks pregnant you are and your individual circumstances.

It is not possible to ‘fix’ or heal the membranes once they are broken.

PPROM and infection

The membranes form a protective barrier around the baby. After the membranes break, there is a risk that you may develop an infection. This can cause you to go into labour early or cause you or your baby to develop sepsis (a life-threatening reaction to an infection).

The symptoms of infection include:

- a raised temperature

- an unusual vaginal discharge with an unpleasant smell

- a fast pulse rate

- pain in your lower stomach.

Your baby’s heart rate may also be faster than normal. If there are signs that you have an infection, your baby may need to be born straight away. This is to try to prevent both you and your baby becoming more unwell.

You should be offered a short course of antibiotics to reduce the risk of an infection, which could cause labour to start.

PPROM and premature birth

PPROM does not always mean that labour will happen soon after, but about half of women and birthing people with PPROM will go into labour within 1 week of their waters breaking. The further along you are in your pregnancy, the more likely you are to go into labour within 1 week of your waters breaking.

You may be offered a course of steroid injections (corticosteroids) to help with your baby’s development and to reduce the chance of problems caused by being born prematurely.

You may also be offered magnesium sulphate once you are in labour, which can reduce the risk of your baby developing cerebral palsy if they are born very premature.

If you do go into premature labour, you may be offered intravenous antibiotics (where the antibiotics are given through a needle straight into a vein) to reduce the risk of early-onset Group B strep (GBS) infection.

Babies born prematurely have an increased risk of health problems and may need to spend time a neonatal unit.

Find out more about premature birth.

Other complications of PPROM

Cord prolapse

This is when the umbilical cord falls through your cervix into the vagina. This is an emergency complication and can be life-threatening for your baby, but it is uncommon.

Pulmonary hypoplasia

This is when your baby’s lungs fail to develop normally because of a lack of fluid around them. It is more common if your waters break very early on in pregnancy (less than 24 weeks) when your baby’s lungs are still developing.

Placental abruption

This when your placenta separates prematurely from your uterus. It can cause heavy bleeding and can be dangerous for both you and your baby. Find out more about placental abruption.

Do I need to stay in hospital?

You will usually be advised to stay in hospital for 5 to 7 days after your waters break, to monitor your and your baby’s well-being.

You may be able to go home after that if you are not considered at risk for giving birth early.

When should I seek help if I go home?

Contact your healthcare professional and return to the hospital immediately if you experience any of the following:

- raised temperature (over 37.5)

- flu-like symptoms (feeling hot and shivery)

- vaginal bleeding

- if the leaking fluid becomes greenish or smelly

- contractions or cramping pain

- pain in your tummy or back

- if you are worried that the baby is not moving as normal. Contact your midwife or maternity unit immediately if you think your baby’s movements have slowed down, stopped or changed.

You should be given clear advice on how to take your pulse and temperature at home. You’ll probably also be advised to avoid having sex during this time.

What follow-up should I have?

You should have regular check-ups with your healthcare professional (usually once or twice a week).

During these check-ups, your baby’s heart rate will be monitored, your temperature, pulse and blood pressure will be checked and you will have blood tests to look for signs of infection.

Your doctor will work with you to make an ongoing plan for your pregnancy, including regular ultrasound scans to check on your baby’s growth.

Giving birth with PPROM

If you and your baby are both well with no signs of infection, you may be advised to wait until 37 weeks to give birth. This is because it can reduce the risks associated with being born prematurely.

If you are carrying the Group B Strep (GBS) bacteria, then you may be advised to give birth from 34 weeks because of the risk of GBS infection for your baby.

Your healthcare professional will talk to you about what they think is best and ask you what you want to do. Don’t be afraid to ask as many questions as you need to feel comfortable and able to make the best decisions about your care.

Will I be able to have a vaginal birth after PPROM?

This is possible, but it depends on when you go into labour, the position your baby is lying, and your own individual circumstances and choices.

Your healthcare professional will discuss this with you.

Will I have PPROM again in a future pregnancy?

Possibly. Having PPROM or giving birth prematurely means that you are at an increased risk of having a preterm birth in any future pregnancies, but it doesn’t mean that you definitely will.

You will probably have specialist care in your next pregnancy. If you are not offered specialist care, you can ask for it. Remember that you can always talk to your midwife if you have any concerns about your care.

Your mental wellbeing and PPROM

Coping with new symptoms, complications or having to attend several extra appointments can sometimes be overwhelming and worry for your baby may cause a lot of anxiety.

It’s important to remember that you are not alone and support is available.

If you’re struggling talk to your midwife or doctor. You won’t be judged for how you feel. They will help you stay well so you can look after yourself and your baby. They may also be able to signpost you to further help and support if you need it.

You can also call the Tommy’s midwives for a free, confidential chat on 0800 014 7800 (Monday to Friday, 9am to 5pm), or email us at [email protected].

Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (2019) When your waters break prematurely https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/patients/patient-leaflets/when-your-waters-break-prematurely/

Tuuli MG, Norman SM et al (2011) Perinatal outcomes in women with subchorionic hematoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 May;117(5):1205-1212. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821568de.

Chiu CPH, Feng Q et al (2022) Prediction of spontaneous preterm birth and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes using maternal factors, obstetric history and biomarkers of placental function at 11-13 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Aug;60(2):192-199. doi: 10.1002/uog.24917.

Dayal S and Hong P (2023) Premature rupture of membranes. StatPearls Publishing https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30422483/

Macdonald, Sue (2017) Mayes’ Midwifery. London, Elsevier Health Sciences UK

Shen TT, DeFranco EA et al (2008) A population-based study of race-specific risk for preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 199(4):373.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.05.011.

NHS Choices. Signs that labour has begun. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/labour-signs-what-happens/ (page last reviewed 19/12/2020 Next review due 19/12/2023)

NHS Choices. Premature labour and birth. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pregnancy-and-baby/premature-early-labour/ (page last reviewed 09/12/2020 Next review due 09/12/2023)

NICE (2015) Preterm labour and birth: NICE clinical guideline 25. National institute for health and care excellence https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25

Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (2019) Care of women presenting with suspected preterm prelabour rupture of membranes from 24+0 Weeks of Gestation https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.15803