Stillbirth and explaining baby loss to children

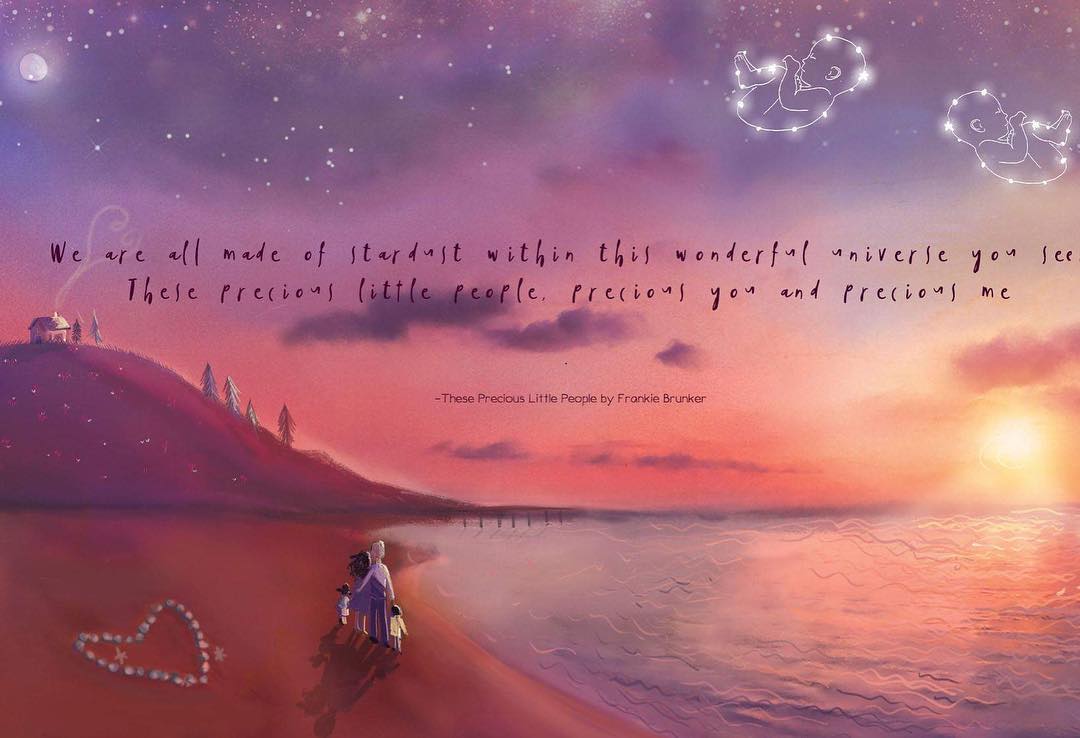

With small children in her wider family, Frankie turned to books to try and explain the tragic loss of Esme - but couldn’t find anything suitable. It was then that she created the beautifully illustrated book ’These Precious Little People’, for families affected by the death of a baby.

The thrill I felt at seeing the ‘positive’ result pop up on the pregnancy test was unreal, and the joy I experienced during the time I was preparing to welcome my baby was the greatest that I’d ever known. We were not totally naïve about pregnancy complications, but seeing our perfect-looking little creation jump around on the screen at 12 weeks gave us a lot of hope and reassurance; my confidence grew along with my belly, week by week.

Every midwife appointment consisted largely of me passing all the checks with flying colours. When I mentioned the baby had been a bit quieter than normal one day recently, they said I must have been too busy to notice the movements so much. I’d actually been relaxing that day, hence noticing the change, but when I pointed this out they just repeated the claim that I’d probably been preoccupied.

My midwife said I could go to hospital to be checked if I was ever worried about my baby's movements - but she also said that if I did it more than a couple of times, I would no longer be eligible to give birth on the midwife-led birthing unit outlined in my birth plan. (As if that was the worst thing that could possibly happen.)

Reduced movement

I didn’t really think anything more of it because the baby had gone back to its full gymnastics routines on a regular basis since then. When we passed the much-fêted ‘full term’ (37 weeks) we really felt we were on the home straight; what could possibly go wrong now?

At 38 weeks and 2 days, my husband returned home from a morning of rugby coaching and asked how the baby had been. It was only then that I realised the last time I'd felt movement was the evening before. We tried the tricks we’d heard were sure to get the baby moving: I drank cold orange juice, lay on my side – nothing.

We rang the labour ward and they advised us to try what we had already, so then they told us to come in and be checked over. We felt a little nervous, unsure of what this could mean. I often describe what happened next as being like an out-of-body experience.

Hearing that our baby had died was a devastating shock: in my memories I am an observer watching my world crumble in front of me, like I am watching myself being shoved violently off a cliff edge and am plummeting into a dark chasm with no chance of rescue.

It being the weekend, the bereavement midwife was unavailable, but we were fortunate to have the use of the hospital’s bereavement suite and were initially under the care of a wonderful midwife who gently explained next steps and encouraged us to go home before returning to be induced the following day. After a mercifully quick labour, I managed to deliver our daughter Esme at 5.39am on Monday 23 September 2013.

No reason for her death

There was no reason found for her death - my placenta appeared completely normal, Esme was perfectly formed and a healthy weight. We spent time making memories with her in the Star Room, including taking photographs and allowing family members to visit, but to me she had already gone – the condition of her body quickly deteriorating being a brutal reminder of that fact.

She was still beautiful but her skin had started 'slipping' and fluid was leaking in places, which was very upsetting to see. I did not wish to linger in that room for too long; it was all so far removed from how I had imagined spending time with my baby after they were born. I was also exhausted from labour and felt totally strung out from the pain relief I had been given.

I knew it would never be easy to say goodbye and I didn’t want anyone’s memories of her to be tarnished by how she looked towards the end of our time with her. I wanted to protect her from anything less than the pure adoration and affection she deserved.

Esme's post mortem results appointment was exactly 6 weeks afterwards. The consultant was only able to confirm that no cause of death had been found, and to this day we are none the wiser why she died. I have since invented a million reasons why it is all my fault.

We told our consultant and bereavement midwife that my antenatal care could have been better in hindsight: I was never told about exactly why it was so important to carry out all the checks, and why pregnant mothers need to monitor fetal movements. Stillbirth was never an issue that I was made aware of.

Being comfortable to discuss worrying symptoms

If my experience with Esme taught me anything, it is that it is so important for midwives to be comfortable to discuss any worrying symptoms that might occur during pregnancy and act upon them when necessary. Do not rely on advice from family, friends or the internet.

If you feel that a midwife is not listening to your concerns, you can ask to speak to another member of the team. If you are still anxious that no one is listening, contact the day assessment unit within the maternity unit, or seek advice from the Consultant Midwife.

Sadly even the professionals can get it wrong - no-one knows your body and your baby like you do.

Explaining baby loss to children and young people

A huge part of Esme’s legacy is These Precious Little People, a beautifully illustrated book that I wrote for families affected by the death of a baby. Many people who experience this type of loss have already included children (siblings, cousins, even family friends) in preparations to welcome a new baby into the family, so it can be very distressing and bewildering for children affected by a bereavement of this kind.

Even if they do not grieve in the way that the adults around them might be, they will almost certainly be aware that people around them are shocked and sad.

Although Esme was our first baby, we had young children in our families who needed to be told the tragic news, and it was very difficult to know how to guide them through what was a confusing and upsetting time.

Straightforward and honest

I turned to picture books for help but I struggled to find one suitable. I wanted straightforward and honest language, with imagery that would reflect our situation and beliefs, but most of what was available back then just didn’t feel ‘right’ or good enough - so I wrote my own.

I was lucky to connect with an experienced, incredibly talented and generous illustrator, Gillian Gamble, who brought my words to life and helped me publish it. It was important to us that the images be ones that all children could relate to, so people from diverse backgrounds could all appreciate the artwork and draw comfort from the words within, as we worked hard to ensure that they reflect the varied range of experiences within the bracket of ‘baby loss’. It’s a creation that we are so proud of.

The children in our family all know about the little girl that made me a mummy. We visit Esme’s grave, we have plants and a tree at home in her memory, we perform acts of kindness in her honour. She is part of our lives still. They ask me questions about her; we speak her name; we all miss her and wish she was here.

These Precious Little People

These Precious Little People is inspired by them, and the desire we share to keep our connection to Esme alive when she cannot be. It lets them know that it’s okay to talk about her and that they are not alone.

All proceeds from sales of the book go to Joel The Complete Package, a small Midlands-based charity that supports families affected by the death of a baby during pregnancy or soon after birth, including those parenting after loss.

Read more stillbirth stories

-

Read more about 'I wrote an email to Tommy’s with shaking hands, sharing what I couldn’t say out loud 'Stillbirth stories

I wrote an email to Tommy’s with shaking hands, sharing what I couldn’t say out loud

-

Read more about 'Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy 'Stillbirth stories

Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

-

Read more about 'I’ve met lots of other incredible dads, desperate to talk, it’s just harder to find the right space to do that 'Stillbirth stories

I’ve met lots of other incredible dads, desperate to talk, it’s just harder to find the right space to do that

-

Read more about 'If love is a measure of a man then Cameron is a giant among men 'Stillbirth stories

If love is a measure of a man then Cameron is a giant among men